The Joneses aim for Siberia

Well hells bells we made it to Russia. After a week got the kids enrolled in pre-school, the dog on hearty Siberian kibble, and found an apartment in Irkutsk, capital of Siberia and our home for the next nine months. All thanks to a Fulbright Scholar grant, that will allow me to research the disappearance of the Russian ship The Neva off the coast of Alaska in 1813.

Here is how we got to Russia.

We set off from JFK on the eleventh of September. Very cheap tickets, no idea why. Stayed the night in NYC, the kids buzzing about not with anticipation about Russia, but rather about opening their “Russia bags” on the plane. An owl and a bee bag, respectively. Filled with stickers, and some red sparkly goo purchased on the boardwalk of Ocean City that I would come to regret.

Had an unexpected and deeply pleasing visit from an Alaska buddy who lives in New York, the awesome WT, who shared wise words by text for our journey: “You are at that terrible crossroads where you’ve walked too far from home to return and the adventure ahead is soooo much unknown. Hang in. Have fun! Love one another.”

And with that sweet note, we were on the Road to Siberia.

Mild traffic on a mild evening along 678 to JFK. Dim reds and purples in the sky. Like the frames of life were slowing down. When I stopped at a BP gas station I watched as a car pulled into the same pump we wanted. Colorado in the back panting. Peeking around for his dog crate, which we did not have, which was very unfortunate, but more on that in a moment. Turned to avoid the head-on collision. A wave. Another gas pump. I felt like I was seeing things clearly. Over the years when I traveled it was mostly alone, or with friends I picked up along the way. No more. A three year-old and a two year-old and a geriatric lab-mix looked up at Rachel and I. We were guiding them halfway across the globe to a frozen tundra. Having started three quarters of the way around the globe, in a rainforest.

The check-in agent at the SWISS desk took one look at our traveling circus, leaned over to her friend and said “Pray for me.” I kid you not, I heard it. Then she allotted us a row of four seats in the middle of the Airbus-330-300. The benefits of pity. I took the dog out for his Last Pee, blessed him, and we went through security. Unsurprised that just about all our bags got pulled for a check, from doggie Ibuprofen from Burgess Bauder to smoothies to the gun I packed to shoot myself if anything happened to my three wee dependent creatures.

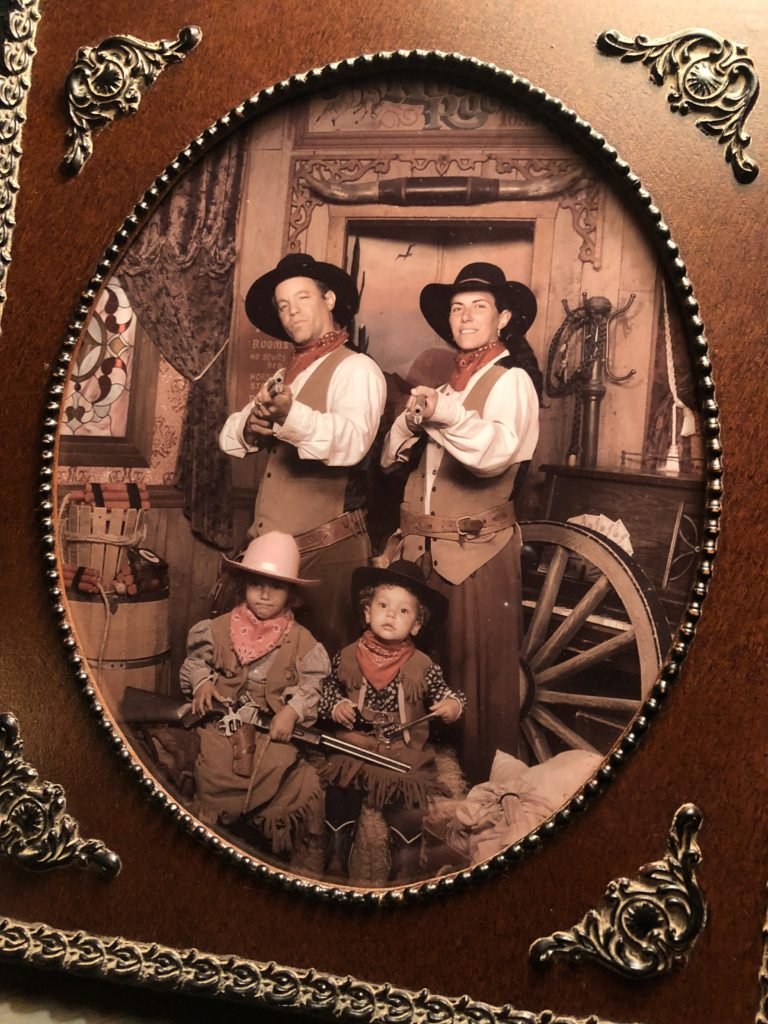

At our gate the girls stood by the window in their cowboy boots – Cow-GIRL boots as Haley always righteously corrects – staring at the plane. Airbuses squatter than Boeings, more compact. We were allowed to board early, the plane spacious with sand-colored seats and individual screens but no soft foot socks I had been anticipating. Put down Colorado’s blanket, hooked the cups for the kids onto the seat pocket and set about getting installed for our pond journey.

Out came the Russian bags. Painting games and googly-eyed stickers, those candies you peel off strips of white paper that reminded me of Great Adventure. And the sparkly red good that promptly got stuck in the dog’s fur, much to his chagrin. A plastic logic game with colored pieces that found all the seat cracks. Through it all Colorado kept his cool. Passengers doing a double-take after seeing him at our feet, thinking perhaps we traveled with a fur rug.

Our departure time came and went. Still glued to the jetway. So much for Swiss timing. We pushed back to onto the apron, then stalled out. It began to hail. The cabin overtaken with that collective feeling of, okay, we’ve already mentally departed from the States, let’s do it for real, and now. The kids must have picked up on it. Kiera-Lee began to squirm, then collapsed beneath the seats in a fit of crying. Haley followed. Off they went like tops. Someone must have told the pilot. The engines fired, and soon enough we were weightless, the shhh of the wing hydraulics as the flaps retracted. Up we went into the rainy night, pushing through the milk-purple clouds to top out over the purple swirl below.

*

For the most part the remainder of the flight went smoothly. Kids gave us one more flip-out after dinner, Rachel staring daggers at me as I watched the Avengers. I didn’t know what to do. They only wanted her. So I watched a movie. Soon the sun rose on the starboard side, breakfast served, more packaging than food itself, and we disembarked into sparkling, sunny Geneva, fountain spewing white foam at one end.

As we disembarked onto the metal stairs the airport crew appeared more worried about Colorado than any of us. They allowed him onto the tarmac (European airports all seem to use buses instead of jetways) and I urged him to pee. Which he did – just as soon as he got back inside. We were prepared with diapers and wet wipes. One of the airport attendants peered skeptically at his urine, and said in French that the dog wasn’t getting enough water. Correct.

The flight to Moscow was in a sun-flooded Airbus A320, mountains to the south, kids doing stickers, Rachel and I noshing on gruyere and Swiss bread made from a Swiss recipe originating in 1896. A happy flight. Baby out. At 215 pm Moscow time we began to circle, broke through the clouds to see tracts of buildings separated by generous clumps of trees. Moscow much less of the sprawling smoggy concrete village I had imagined.

Once again, a bus. At immigration we got in trouble for trying to get into the country undercover, as it were. (Our passports were required to come out of their color-coded holders.) With a humph they stamped us in. At baggage claim we stood for some time before accepting that Rachel’s bag with all her clothes didn’t make it. As I searched and accosted people with my Russian Haley made a friend with a Russian kid, the promptly popped his balloon, which he didn’t seem to mind. I ended up somewhere in the bowels of the airport in a brightly-lit office where a woman said the bag would be sent to us once we arrived in Irkutsk. No Swiss desk or any desk for any airlines, for that matter.

At pet migration a nice older fellow in dress blues and epaulets reached down to pet Cal, glanced at our papers, felt the embossment from the USDA, and plunged his stamp. That’s how it goes. The power of the stamp.

Moscow’s Domodedevo Airport felt small, and manageable. We considered getting a bite to eat, then decided to walked over to see about checking our bags. We were flying S7, a Russian airline which favored neon green as a color.

First off, there was no reservation for Kiera-Lee. I shuttled between the desk a couple times, attempting to show the Expedia reservation, which was useless because it wasn’t in Cyrillic. Finally got that one figured out, and thought we were good to go. Except the dog. Service dog? Certainly not. He would only be allowed as luggage. We had no crate. What to do?

I returned to pet migration to half-mime, half-explain our problem. The kind man in his epaulets appeared straight from Russian central casting as he furrowed his brow and considered. I followed him into a storeroom, where he dug out a dog crate for a large terrier. I shook my head. Deeper still, pushing aside bird cages and cat carriers. He reached up against the wall to pull out a compressed dog cage, which I brought back to measure against Colorado. It would work – as an oversized muzzle.

What could be done?

The ticket agent, pale blond, pretty and stubborn, looked back at me. Wondering. I recalled the ticket agent in NYC telling her friend to pray for her. This woman did not seem the praying type.

She rummaged around her desk and found her cell phone. I knew the word moosh well because Rachel continually tried to say it into our Russian translation app without a Jersey accent, setting the “U” sound where there should be an O. It became clear to me she was calling her husband to see if he could find a clietka, a Russian dog box. Fifteen minutes passed. He couldn’t. Could we stay the night in Moscow? We couldn’t. We were at an impasse.

I jogged the airport to pet migration. The kind older man, wondering if he had perhaps skipped over a dog crate that would fit a 65-pound dog, returned to his closet. Nothing. A woman in a jean jacket waiting for a doggie passport searched her phone for a pet store that might still be open. It was coming up on seven at night. The three of us stood in that small office as she called one store after the other, searching for a large clietka. And then she found one. If I could wait while she finished her doggie passport for the beagle, she could drive me into the city, I could purchase the clietka, and take a taxi back to the airport.

It was 7:15 pm. Outside the sun set. Our plane boarded at 9:10. We had given ourselves seven hours between arriving at the airport and catching the next flight. It would appear we’d need each one of them.

I paced outside the office, repeating the Russian phrase I am so sorry but maybe I should take a taxi. Then the door opened and she emerged, buttoning her jean jacket, pushing her glasses up her nose. Shy, 45 perhaps, a doppelganger for one of my step-sisters. Davai, she said. Let’s go.

The revolving doors ejected us into an evening where the clouds seemed sanded down, purples and pinks reflecting off the ragged edges. Streetlights craning over the give-lane highway with no shoulder, as if trying to peer inside vehicles. Despite the orange Ladas parked at all angles and the buses and shouts the air smelled fresh. Scrubbed. The terminal behind us mirrored blue and eerily peaceful. I followed, a step behind as she switched through the labyrinth of vehicles, either dusty Ford vans or Land Rovers and BMWs. We walked the side of the highway – which struck me as strange.I asked about her dog, who now had a passport. Killer, she said, and a chill went up me. A gray Land Rover pulled up along the shoulder. She pointed. The front door swung open. Davai, she said. “You go in.”

Vehicles rushed past. At the wheel was a big man, forearms like squashes. He gave a small nod. Well, fuck it. I got in. She sat behind me, which I didn’t like after having seen the Godfather too many times. (Cannolis etc.) I considered, for a moment, saying niet pajawsta and just stepping out of whatever web I thought might be weaving around me. She had seemed so nice.

Then we were accelerating onto the freeway, the man’s Russian as fast as the eight pistons jamming beneath the hood. Blue highway signs the size of barn doors flashing by. “Killer,” she said, pointing behind his seat. A heap of beagle snored away in the wheel well. So that’s why she sat behind me.

It went dark as if someone had flipped a switch. His half-filled soda in the cupholder appealed to me, whatever it might be. It had been hours since I had a sip of anything. Outside Cyrillic appeared faintly familiar, but by the time I got a letter or two it was gone. The soda in his cup holder, the soda. I want that soda. From the back my friend said, “About 15 minutes to the Torgocenter.” The sound of “target” put me on edge again. Full night now. We came upon a lit up box building with various signs affixed to the skin advertising stores. He stopped in traffic and we jumped out onto the sidewalk, into the neon-lit hallways. Small, neatly-arranged kiosks selling blenders and chainsaws and flowers and balloons. Farther inside the warren my friend asked this person then that directions. Finally, a few floors beneath the earth, coming upon a pet store the size of a newspaper stand, packed to the ceilings with dog toys and bird cages and bones. And there, in the hallway, a single, huge, gorgeous clietka.

The salesperson offered to put it together, but we both demurred. I paid 13,900 rubles for it – and we hauled it together up the stairs out into the night air. She approached a few cabs parked nearby, called the number of one but folks, intimidated I think by the clietka – I doubt it could fit in a back seat – wouldn’t budge. It was 8:35 pm by this time.

And so she called her boyfriend or whatever he might be. He came back around, stopped in traffic, and we stuffed the box in. Back to the airport, where he took ticket for entrance into the airport, which I offered to pay for but he waved me off. Stopped in front of the terminal. I petted Killer goodbye. He helped me lug the crate out. I only had dollars so took out sixty and he shook his head. I pressed the money on him. He smiled, and I’ll never forget this. He said, Please, man. No.

My friend in the jean jacket had stepped outside the vehicle. It seemed they were ganging up on me to make sure I did not pay. And then came the words – here I must thank the most extraordinary Russian teacher Marina Pelmeneva for her instruction – Pervy vrema na Russia, nemoverny. Bolshoe spaceba. First time in Russia, incredible. A big thank you. I asked for her email but she waved me off. And they disappeared into the night.

Back in the departure terminal the kids and Rachel spread in front of the counter like refugees. Haley sleeping in a knot of sweatshirts in the corner. The dog confused, tied to the luggage cart.Kiera-Lee climbing over Rachel, in her green dress, who had somehow managed, with one animal, and two kids, to get food – a bowl of olives and cheese. The check-in attendant who called her husband clapped when she saw the clietka. She had stayed behind instead of going home to make sure we were okay. I hugged her, the softest hug. There was a minor crisis as everyone tried to determine the cost of the clietka to put in the belly. Hell, I hadn’t even figured out how to put the dang thing together – instructions, of course, in Cyrillic.

At nine o’clock we barged through security and ran. The dog packed away somewhere with food and water in his 13,900 ruble clietka. Down one flight, then the next, Haley’s cowboy – girl – boot falling, picking it up, running again. And there was the crowd by the gate. Our flight delayed. Haley found Russian treats for the plane, which would be six hours above Russia, larger than the man in the moon. I got a bolshoe bottle of water. Kiera-Lee flailed on the floor. We boarded early – we didn’t have to jockey for it, but were led on by an attendant – got installed, were immediately given a backpack of kids’ toys. I started to get the sense, even in my blitzed state, that Russia liked kids. Understood them.

The plane lifted off from Moscow, we were given a pasta and chicken of some sort that tasted like salted cardboard, along with a KitKat bar that tasted like god herself. Five time zones we crossed. Touching down the following morning in a snowstorm to Irkutsk airport. Skeleton of an old airplane by one runway, which reminded me of crashed floatplanes on the approaches to lakes in Alaska. Snow whipping around as we walked down the stairs and boarded the bus, not having to hold on because we were so squished. Kids pale with sleeplessness. Twelve hours off east coast time, fifteen of Alaska. Delirious.

We met our contact, Assia, with orange hair and a scarf and warm smile. Colorado came out. I asked for scissors in Russian to unclip the zip ties. That was awesome. The dog promptly peed over the floor by baggage claim, to the horror of the Russian customs agents. At a certain point, when you haven’t slept, and the kids haven’t slept, and you have been traveling for close to three days straight – it just didn’t matter. I used a couple kids’ diapers to clean it. Really didn’t care.

Assia told us we would need 24,000 rubles in cash, a surprise. We withdrew 5,000, but that was the limit from the ATM. She would lend us the rest to pay for the apartment.

We followed Assia into a white cab, windows were clouded with fog. Haley silent and watchful, she loves the snow. Always has. Schniek, she said. Snow. Indeed.

We unloaded at a shell-colored apartment building. The snow going sideways. Jammed bags and dog and crate and kids into the elevator to the tenth floor. Found a small but comfortable apartment with two room. Exchanged money, people left. We pulled the shades, fed the kids water, and we slept, all of us, until evening.

We were twelve hours ahead of East Coast time. Sixteen hours ahead of Alaska.

After our long hibernation we woke, late. 7 pm. I went for a shop, and found blini mix. Very important. My great grandmother, Bella, from Russia, made blinis. My grandfather Isaac I am named after. It made sense.

And so I set my daughter, who has my grandmother’s name – Julia, who was born in Russia – on a stool, and we made blinis with some of the best butter I have tasted. Of course Haley took right to it.

We had ten days to find an apartment in town. In the meantime we had a playground scoped out, right beside our building. We had blinis. We were together.

The adventure had started.