Silver squiding it across the U.S. part I – Ohio to Texas

We left ourselves with the last post, I believe, on a grassy knoll about 30 miles from Dayton, near the town of West Liberty, in Salem Township, Champaign County, Ohio. Citronella candle burning. Trying to figure out whether to turn south towards New Orleans, or continue through the Midwest along 70, trading off the doldrums of Kansas for the peaks of the Rockies. Thus taking the straightest, and most sensical line across the country.

Before any of that, we needed to go to the Airstream factory. As we were coming to learn from Airstream Addicts, the endlessly entertaining Facebook page, craftsmanship on these silver torpedoes had dropped off in the last ten years. Expect something to go wrong on your unit – especially if it was bought new.

In our case it was the rear hatch door. It didn’t shut correctly. It was a big ticket item, and on a unit that brags about being airtight, seeing daylight through the cracks wasn’t cutting it. When we got the Squid up to Sitka, we’d need a sealed envelope. We tried adhering foam along the edges, but that was only making it worse.

On top of that, the refrigerator wasn’t refrigerating correctly. A label looked as if it had been peeled off a used Airstream. The shower door didn’t shut, hinges weren’t adjusted correctly, screws in the oven weren’t set.

Anyone who has driven through Jackson Center, Ohio, has seen the Airstream Factory, because it’s pretty much the only thing there, aside from a gas station or two. The factory painted the same bright blue as the sky Dumbo haplessly flaps through, with “Airstream” stenciled onto its stacks. Each September, Jackson Center is turned into one big mirror, as thousands of Airstreams convene in the small town for the factory-sponsored “Alumapalooza” – that’s what they call it. A gaggle of oversized toasters in cornfields, the median age of town skyrocketing for that week.

Sadly, tours at the factory been suspended. Also sadly, the New Hampshire store where we picked up the Squid had failed to give the factory a heads up, and the garage was pretty well booked. After some back and forth, and displaying Rachel’s pregnant belly, they found their door guru, who agreed to take a look at things. We would need to stay overnight for the work to be completed, he said, on the “Terraport” – a collection of free RV slots.

That evening as the sun set, we walked through a collection of Airstreams in the lot, all awaiting service. From older models in the fifties and sixties, to the sleeker – but still classic-looking newer models. Weaving through the units, you could track the evolution of the company.

Before taking this voyage, I had been in touch with Airstream’s advertising company about blogging for the company. They had shown significant interest, and had offered a unit to cross the country for free, and were considering giving a significant discount if we bought. Then I posted something on Facebook about the MOVE fire in Philadelphia, and Black Lives Matter. That email thread dried up quickly.

I thought about this now, as the kids slipped between the aluminum units, playing hide-and-seek. I felt glad not to be burdened with the responsibility of saying only nice things, or any responsibility to any company as I wrote. There seemed to be enough compromises in the world. Or to keep things apolitical, especially in this moment. I was lucky enough to be sheltered away with my kiddos in this pod, while others were out demonstrating, working for needed change. I’ve also never been good at holding my tongue.

Sponsorship or not, I loved the story of the company. How Wally Byam, whose grandparents came west along the Oregon Trail in a mule-drawn wagon, lost his job in 1929, and took to the road with his wife Marion. When she complained about sleeping on the ground, Byam, who was raised in a wooden wagon towed by a donkey on a sheep farm in California, built a shelter atop a Ford Model T chassis. The tent leaked, and Marion was unhappy. So Byam developed a tear-shaped, more permanent shelter, with a stove, water reservoir, and ice-chest. The idea caught on, and Airstream officially opened its doors in 1931. I mean, it’s a family story of compromise. So perfect for the moment.

It was Rachel’s suspicion that, with COVID, people across the U.S. were looking for groups to belong to. We got one of the last units available, totally lucking out to land one with a rear hatch. Airstream’s stock price doubled since the WHO called the virus a global pandemic in March. Younger families like ours were interested in the solar panels and heat units – you really never would need to plug in, except for draining the tanks. And also, Rachel was probably right. If you’re determined to join a cult, one that worships aluminum sausages with four wheels isn’t such a bad one.

Dusk fell. The kids flitted about, appearing and disappearing behind the trailers. “Wow. You see this?” Rachel asked. She stood in front of a wreck of an International Serenity, a model similar to ours. We peered in the windows. Broken glass all over, just a tangle of aluminum, and plywood, gray shards strewn across the floor.

“Yeah. We’re not traveling in this trailer while it’s under way,” Rachel mumbled.

Airstreams are light for a reason: they’re lightly built.

The next morning we woke with the sun, sitting at the table, returning to our immediate future over coffee.

“What do you think?” I asked her. Our friends were standing by to hear in Nola. I was standing by to plot a course.

“Definitely the smart thing to do is head west.”

“I know.”

I pictured our path, along with the odometer on the Blue Moose at the end of this trip. Would our line across the United States look more like an EKG chart, or a dead person’s? That was the question. Justin had just texted to say that Charles was heading to school, and this worried Rachel. We also desperately wanted to see them – and I wanted to see my godson. Haley wanted to see Mt. Rushmore, though I knew she’d gladly trade those four carved white dudes for a visit to New Orleans, to see Baby Charles, her godfather, and family.

A John Deere rumbled over, breaking up our conversation. It was 7:45 AM, and the tractor was ready to pull the Squid back into the garage, so they could finish up their work on the back door. We put the conversation on hold.

Inside the waiting room we were told another two hours. As the girls ran around, Rachel and I settled into the den-like waiting room, ready to take up the conversation again.

“You all must be having such fun,” said a white-haired woman in a golden visor, with a matching golden retriever at her feet. “Your girls are darling,” she said, in a clear southern accent.

Rachel didn’t respond. Little had been bugging my wife off more than people saying what fun this trip across the country would be. She was pregnant, and sitting was difficult. We had a three and five year-old. A pandemic gripped the nation.

“I hate this virus,” Rachel said, turning to me. “Let’s go see friends.”

Thinking about it now, from where I sit in this basement in Seattle, that morning in Jackson Center set the tenor for the rest of our trip, if not the rest of our pandemic. Instead of saying No, and remaining in our aluminum Faraday cage as we crossed the country, we committed to a constant program of risk assessment. This virus was not an absolute value. Cocooning the kids off – as good as it might make us feel as parents, knowing we were capable of keeping them safe – was not in their best interest. These were their lives, after all. These were their childhoods. We’d be like Tony the Toucan or whatever that Fruit Loop bird was called, following our nose, but also making informed decisions in the effort to give them some sense of normalcy in a tough moment. Some memories not created on a Zoom, or indoors.

Also, we both really wanted drive-through daiquiris and po-boys.

“You sure about this?” I asked, as we cruised down 75 South, approaching the exit for 70 West, which would take us across Kansas and through the Rockies. The dashboard read 97 degrees outside. In the back seat the girls sang Hark the Herald Angels Sing. “We’re committing to a lot of heat. And road hours.” We wanted to make the weekend, to get some relaxed time with friends.

Feet propped up on the dash, black tanktop and bejeweled sunglasses on, Sicilian skin dark with the sun, Rachel nodded. “Sure.” She had bought glasses with plastic diamonds in them, so that I wouldn’t steal them. Also a pink charging cord. I could care less if the glasses had diamonds on them, though I knew this would get more problematic the farther south we went. Diamond sunglasses on a man doesn’t fly in an Alabama gas station.

As we drove, I opened up an email from my editor at Random House, typing back an address for her to FedEx her edits on my YA novel. I knew the publishing industry was one big dinosaur, but apparently scanners weren’t working. Which was fine – I looked forward to seeing the pencil edits, and sent on the address in New Orleans.

That was that. We were locked in. The Big Easy it was.

We checked in with our trusty Harvest Hosts App, and found Jordan Hills Farm in Richmond, Kentucky. Southeast of Lexington, not far from where I once lived for about six months, on a cattle farm. The blustery wind that shook the trailer on the interstate died down on the winding back roads, not much wider than the Silver Squid herself. It all felt familiar, leafy and dappled with shadow. I kept the measurement of just under ten feet in my head, for fear of taking off an AC unit, or two. A loss that would make my entire family very, very unhappy, and probably mean a change of course.

Haley yelped at a sign for Jordan Hills, and I made a quick left into the farm. A woman waved both hands as we arrived, in what appeared as a particularly enthusiastic greeting.

“How good are you at backing up?” she asked, with a slight drawl. “You’re further up, at the top of the hill.”

Whoops.

We threaded two small fruit trees, backing up into her grass, traveling back out the small road, doing a 24-point turn into a driveway, then trying the approach once more. The skid plate scraped we pulled into a gravel lot overlooking her farm. First blood on the Silver Squid, and we all gathered in the heat to examine the damage, the slight twist of the bumper, contemplating.

“Had to happen sometime,” Rachel observed.

J let us use her hose, and the girls quickly engaged in a water fight. J meanwhile told us the story of losing her husband three years ago – “the jerk just left me.” We sat on a stone bench to watch the sunset, with laminated Polaroids of the two of them – much younger, as high school sweethearts, shellacked into the stone. His gravesite just visible down the hill.

Rachel washed clothes in a bowl, hanging them to dry, and exchanged a few words about possible hurricanes in Mississippi with some folks in a rental RV. J arrived in an orange Kubota 4-wheeler to ask if any of us wanted haircuts for ten dollars. Haley and Rachel disappeared above the garage, where J had a single seat, while Kiki and I tumbled along the hill beneath the sunset. A cool wind blew up through the hills as Kiki chased her ball down the hill. Haley and Rachel emerged from the garage, newly-coiffed, my dreadlocked waif turned into a cute little girl with straight, blow-dried hair.

As Haley marveled at herself, J, close to tears it seemed, told us how Kentucky unemployment had yet to even kick in. Her contractor, who had built her barn, was also building her retirement home, and had stiffed her. She was taking him to court. The farm, which she had originally purchased as a wedding venue, had been useless since COVID. J snapped out of it, recalling that Kiki wanted a ride on the Kubota, and off the two of them went.

The following morning we waved goodbye to J. We had a big day of driving ahead of us, hoping to make it to Crossing Creeks Farm, in Shelbyville, Tennessee. I had an article to finish, and Rachel had law work to do. We purchased a printer that worked on a battery, allowing us to make the front seat into a mobile office. We rumbled off the gravel pad, this time without tweaking a bumper, threading the windy Kentucky roads, picking up 75 South once more in hopes of making a farm that sold raw milk, and offered a plug-in for $20, which meant we could use the AC. Hallelujah, Rachel mumbled, as the girls once more took up Hark the Herald.

The heat was becoming overwhelming. Climate refugees made total sense – this heat unbearable. Justin sent good news that AC had just been installed in the room where we were staying. Still, the mugginess was becoming rough. And we weren’t even in the worst of it, with Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas still ahead of us.

When Hark the Herald got to be too much, I introduced the girls to “Dixieland Delight,” a song by the group Alabama. As kids my sister and I shouted the song out, and it continued to be one of our go-tos. Since we were going into Tennessee, it only seemed appropriate.

Rolling down the backwoods Tennessee bighway, one arm on the wheel.

Holding my lover with the other, A sweet soft southern thrill.

The lyrics, which had brought me such joy as a kid, now gave me pause. Hard to imagine the good ol’ boys of the group Alabama giving .02 about the BLM movement. What were the ethics of teaching my daughters these lyrics?

Worked hard all week

Got a little jingle

On a Tennessee Saturday night

Couldn’t feel better

I’m together with my dixieland delight

One thing was for sure – the girls couldn’t get enough. Soon as the song ended, they wanted it again. They belted it out, playing their imaginary fiddles on their shoulders, their carseats jolting from side to side. Kiki had a fiddle in each hand, which makes sense considering she’s never seen a fiddle in her life. A heated discussion began in the front seat over whether a fiddle was the same as a violin. (It is – different tunings.) It also made me recall singing the same song for Karaoke in Red Hook, in New York City, and going down in flames. Crickets in that small bar. Wrong choice.

It was hard to enjoy the song as I once had, despite the stomping of Kiki on the back of my seat. Feeling the undercurrents in the music, a yearning for the antebellum days in the south. The music blared as we made our entrance into Crossing Creeks Farm.Two boys, about 11 and 7, watched as we looped the Silver Squid around to the plug-in, which Rachel eyed with glee. The 50-amp cord went into the stand beside a sled of freshly-picked onions, and the two rooftop units rumbled to life. The girls made a beeline for the farm store, which Elizabeth, who ran the milking operation, had kindly kept opened for us. The store immaculate, with sapphire ingots of beef shining behind spotless panes of glass. Between that and multi-colored eggs and a mysterious salt-dust Elizabeth swore would make all food taste good, we were set for the evening.

We woke early, the girls having secured an invitation to cow milking. Just after 7 am two Guernsey cows were brought over to the barn, their udders swaying side to side. One by one they were given fresh hay, and duly hooked up to a vacuum-powered milker. The older boy ran around with his oversized dustpan, keeping up a running dialogue for the girls as the machine hummed away, telling Haley and Kiki what he was doing, while his mother worked the machinery in a separate room, safe from bacteria. The farm, we were told, could not sell raw milk. But they could sell pet food. We were all eager to drink pet food that morning, with heavy cream on top, and purchased a jar for 8 dollars.

After that, still in the company of our eager guide, we slopped the pigs with the fresh cow milk. The pigs, after drinking, bathed in the milk, the temperature already approaching 100, though it wasn’t yet 9. Then we fed the chickens, and the ducks, and retreated to the cool Squid for a breakfast of duck eggs, fresh bacon and fresh pet food milk. Feed the animals, eat the animals.

Bellies full, we hit the road again – playing On the Road Again, of course, followed by Dixieland Delight, at the girls’ insistence, fiddles out with a vengeance. I thought of Black friends from growing up in Philly, and tried to hear what they might say about Alabama. Scared, that’s what they’d be, of ever going to the state, was the best I could do. And the music? It would have nothing for them. Except maybe my friend Alfie, who liked Country. He could find beauty in anything.

Signs for U.S. Space and Rocket Museum in Huntsville, Alabama, sent travelers into the Blue Moose into revolt. Biggest rocket in the United States? Had to be seen.

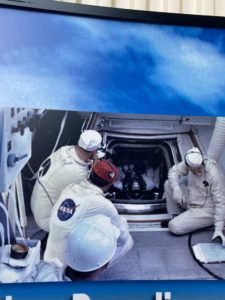

We pulled the Silver Squid into the nearly empty lot, and trudged through the muggy air to pay entrance into a museum that was actually pretty cool. Huntsville where the rockets for the original spaceship to the moon were built. A unconvincing replica of the lunar lander was there, looking like a class project on large-scale, with its gold foil and spindly feet. The girls maneuvered between the roped-off interactive exhibits – you couldn’t sit in the pod the astronauts used for blasting off, or really do anything that involved touching.

We did come across the Airstream that was used to quarantine the astronauts when they came back to earth – apparently the trailer had disappeared for a while after use, only to re-appear a couple decades later at an Alabama fish hatchery.

The Airstream used because it was airtight, and self-contained – any bacteria the astronauts might have brought back from the moon wouldn’t be released. Rachel liked this exhibit very much.

We also came across a photo of the astronauts preparing to launch into space, with the engineers grouped around the pod, with a roll of duct tape in the top left-hand corner. No joke. Probably not what you want to see if you’re an astronaut preparing to go into space.

We left the velvet air-conditioning of the museum, stepping back into the sweltering heat. I pulled the Silver Squid around the front, and we got back on the road, with Haley asking all kinds of questions about how old you need to be to be an astronaut, and attend NASA’s “Space Camp.” Kiki was more concerned with getting to Stroka Gene-Us Alpaca farm in Mississippi – this had been her destination of choice back in New Jersey. Haley still had the lavender farm in Texas in her sights. Kiki had seen an alpaca that looked suspiciously like a baby giraffe, and was determined to investigate. (Rachel, for a brief second, was very into Tiger King on Netflix – we knew the south was a hotbed for unexpected creatures, so why not a giraffe?)

Along the way we stopped at a fruit stand to stock up on peaches, some of the sweetest peaches ever. After getting parked in, I jacknifed the Airstream in the parking lot, which was awesome. Peach juice was general on the faces of our girls. We had a new dent in the truck. We both had fallen behind, and needed time to work to start recouping expenses, and sincerely hoped that the alpacas would babysit at this upcoming farm.

An ashy evening had fallen over Mississippi. The shoulders of the roads fell away, replaced by sand and crumbling asphalt, as as we made our way toward to the alpaca farm. There had been a storm, we learned, that had ripped through a couple months before. Crickets screamed as we passed low-slung brick ranch houses framed by twin flagpoles, one flying the American flag, the other the Mississippi flag – which had the Confederate flag in its upper lefthand corner. We passed a few houses flying a blue flag with a single star on it. What could that be? The Bonnie Blue Flag, which Mississippi used when it seceded from the union in 1861. I guess the Confederate flag, and all it stood for, just didn’t make things clear enough.

It was just after dark when we pulled into the dirt-sand driveway of the alpaca farm. The humidity was deafening. The grand-daughter of the owner greeted us in clunky rubber boots, waving us over to a spot beneath some spindly, shortleaf pines. None of us were hungry. The upholstery of the cushions stuck to our skin. The girls drank a few glasses of water, brushed their teeth, and squirmed in the beds, uncomfortable with anything touching them. It felt like being at the bottom of a swimming pool, and reminded me, out of all the places I’ve been, of Cambodia. No matter how hard we tried to keep the doors closed, mosquitoes seemed to find their way in.

I looked at Rachel, whose brow was glazed with sweat. Had we made the right decision? She liked the dry heat. But this – this was something different.

“This place feels haunted,” she announced.

The next morning Haley and I woke before the sun. I found a couple quarters to put into a dispenser of alpaca pellets, while Haley just reached into the broken plastic to take out a handful. They were stale, and the alpacas, who had wandered over when they first saw us, turned their backs to them.

The granddaughter of our host greeted us, back in her impressive boots, and started the sprinkler system, which the alpacas luxuriated in, soaking up the cool. We learned that our guide was a drama major, with a dim future, she explained, because theaters would never be full again. The girls watched, hypnotized as she showed us the tools for making alpaca wool.

“Do they get cold after you shave them?” Haley asked.

“Not down here they don’t,” she answered.

After picking out a few alpaca gifts, we bought some fresh eggs. As we were leaving, she warned us that there were roosters in attendance. “Don’t be surprised if you crack one of those eggs and find a chick inside.” Rachel went white.

“Oh my God,” she said, as we crossed the grass to the Silver Squid. “That better not happen to us.”

“Adds a bit of drama to breakfast,” I observed.

From the land of alpacas we continued our line southwest, stopping in a small town for fried green tomatoes beneath magnolia trees, sweet tea, cookie dough served up in cones like ice cream, and a good look at a white marble memorial lamenting fallen Confederate soldiers.

I knew that my own family on my father’s side had lost three brothers in gray in a single battle. The idea that there had been slaves in the family haunted me. I had recently read a book by the same name – Slaves in the Family, by Edward Ball – and researched through Ancestry.com the census. All on our side dirt farmers in South Carolina – though we were distantly related to a man also related to Robert Duvall, Barack Obama, Dwight Eisenhower, and Dick Cheney – a French Huguenot who had twenty slaves. So there was that. We also had rights to join the man’s exclusive society. I found myself wondering if Barack Obama had done so, and guessed probably not.

Onwards we flew, crossing into Louisiana, the air taking on a tinge of salt, and a welcome breeze blowing up as we neared the Gulf. We pulled into New Orleans, the streets impossibly small, squeezing between cars parked on either side of the streets. We had not been to a city since starting our journey – and wouldn’t be hitting another one with the Squid before Seattle. Once more we questioned our decision.

Airstream, at Nashua, had neglected to give us the back-up camera that comes with the unit.So Justin backed me up into his narrow driveway, only scraping the wall – and our Airstream – once. And thus began a blessed long weekend, our friends cool as could be, the kids playing, a soft landing for Rachel – everyone clearly of the belief that the moment demanded kindness and generosity, and not flipping out about the kids getting too near to one another, or eating from the same bowl of potato chips. We walked the tracks in the heat to the Bayou. Strolled the sidewalks, just to get out of the Blue Moose and walk – the kids were happy, Haley continuing to refuse to take off her Alaska puffin shirt. We even went with Justin and Dana to vote at the local church, the walls of the mint-green cinderblock – which of course reminded me of every single apartment stairwell in all of Russia, covered in photos of prominent black Episcopal priests. We made yummy breakfasts, everyone holding their breath as we broke open our Mississippi eggs, to see if their might be a little bonus baby chick inside.

And, of course, we got our daiquiris. Rachel had a few, not very big sips. Welcome to New Orleans, baby.

On Monday, our last day, my manuscript, marked up in pencil, arrived. We said our goodbyes, spending about an hour getting the Airstream onto that small street, hitching and re-hitching to get the angle right, and were back on the road – to Lake Fausse Pointe State Park. Rachel fretted about alligators – and rightly so. A couple trolled beneath a bridge, looking up expectantly at the girls. We walked the trail through the woods, battling against mosquitoes, learning all about armadillos, and how they can armor up.

We occasionally got a bar of cell service. After the kids were asleep Rachel went outside to try and make a call, and came running back in a few minutes later, screaming, “Are red eyes predator? I think an alligator just stalked me on the banks.”

We learned the next morning from our neighbor, an old Cajun dude barely comprehensible, that indeed, a baby alligator had been crawling behind the RV pads.

All over there were “Don’t feed the wild animals” signs.

“Everything wants to kill you or drink your blood down here. You don’t have to feed them. They’re trying to eat you,” Rachel observed.

Meanwhile the park rangers at the entrance were having beers and feeding the raccoons, which grouped up in the evening for their dinner. I just don’t think our two minds could make sense of the contradictions inherent in the land. It took a sense of humor – and whimsy, perhaps – that apparently we did not possess.

Perhaps to get a sense of the reasons, we got a swamp tour, and met an even larger alligator who loved cheddar peanut butter crackers. Meanwhile, to Rachel’s horror, boating families passed by pulling their children on inflatables. “This place is too crazy for me,” she announced. “Cotton mouth snakes, fire ants, mosquitoes, alligators that chomp you. Snapping turtles. What’s the appeal?”

“Maybe the British just dropped you off, and there were no better options?”

After a couple nights at Lake Fausse, we continued west now, toward Texas. Stopping at Rita Mae’s Kitchen for some incredible sweet tea and peach pie and beans and rice. Checking Harvest Hosts, and finding a winery on Oak Island, Texas. A place I never new existed in the world.

On we went, stopping for some crawfish along the way, because it seemed to be all anybody sold. With this mysterious island in Texas our goal – the winery apparently known for a drink called Dragon Fire, a spicy mead – we continued on.

Within minutes of driving onto our grassy field in Oak Island, Texas, a golf cart pulled up, driven by a man with no shirt, and his pretty wife, with three kids in tow. This was Ricky and his family. As I learned, Ricky had been a union carpenter in New York City for his whole life, living in Northern New Jersey. Working mostly on skyscrapers. He got laid off, and the family piled into an RV to go to the Shore – not far from Ocean City, where Rachel went as a kid. Then they just kept on going west. The kids had only a couple changes of clothes. But they didn’t want to go back home. So here they were, on this winery in Oak Island, Texas, just across from Galveston Bay. Ricky was working for $10/hr for the owner of the winery, they had been here for just over a month, with no plans to go home.

“What’s left for us?” Ashley asked. “I want to go west.”

They invited us over for S’Mores that night, and we headed over to their RV at just after ten. They roused, and before long we were all by the fire, drinking moonshine, learning the finer details of their escape from New Jersey. Asking about our situation, comparing notes on vaccines, whether to drink milk, what was really up with this virus. The girls were huddled together in their little chairs, conversing by the fire, stuffing themselves with marshmallow. Once again, happy. Goal achieved.

The next morning, achy head, walking toward the water, we learned the entire story of Oak Island from a fabulous Venezuelan man who took one look at our family, and brought over five bottles of water. He was in the middle of painting a mural on his own RV. As we sat in the shade of Spanish moss, he told us about the hurricane that had swept through Oak Island, and how misfits had re-populated it. He was supposed to paint a mural for the owner of the winery, but then they had a huge falling out. He had visited Norway many times, and perhaps wanted to settle there. The woman who ran the winery had arrived here in her RV with her husband, who had treated her very badly. The owner of the winery intervened. Now she worked at the front desk of the winery, her husband was gone.

“You should probably leave,” he counseled us earnestly.

“This place feels like a vortex,” Rachel observed, as we watched the sun set on the pier. “I don’t think we should get sucked in.”

However this tune changed on our third night on Oak Island, when it became clear that we could plug in, and thus fire up the air-conditioning. Suddenly Oak Island, and its drama, wasn’t so bad.

Especially because the girls had a crew to play with. There had been no cases on the island. There were no alligators here. Heck, I could even help Ricky with carpentry, and make some money.

“I could actually see staying for a little,” Rachel observed, as the kids played.

“We’re getting sucked into the vortex.”

“I know. We should leave.”

“Yeah. We should.”

“But the kids are so happy.”

“I know. They are. Maybe we should hang around.”

The tour of the winery finally goosed us. The vines were withered, and the wine-making tools were in disarray behind the welcome desk. The man who ran it – incredibly kind, generous and welcoming – was having medical trouble. The woman who showed us around, who had remained (all this according to our Venezuelan friend) on the island after her husband left, knew little about wine-making. Haley’s question on how corks work left her stumped.

And so we made tracks, pushing northwest into Texas, toward Haley’s lavender farm. We spent a night in an RV park just outside of Houston, before following the scent of lavender through the dry heat. Off a dirt road we were greeted by a man on an ATV, who smiled broadly as he led us under a collection of live oaks, just beneath an old well.

“You girls ever seen someone with one leg?” he said, reaching down to pop off his prosthetic. Haley’s jaw drop. Kiki marveled. When he got no response, he followed up with, “You girls ever seen longhorn cattle?”

And then they were off, riding on his ATV, leaving Rachel and I swinging beneath the live oaks, bathed in a water mister his wife had kindly brought over.

“Better than Oak Island?” I asked.

“That was a narrow escape,” she observed.

I followed the kids over to the cattle, to make sure they didn’t get gored, which wasn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. They were already at work, tossing hay to cows, and to a couple braying donkeys. Their dog Rocket, an uncharacteristically stupid Aussie Shepherd, wouldn’t stop diving after his own shadow. The girls greeted a couple horses who came over, looking for food, including a beautiful palomino.

We stayed a single night at the farm, then pushed off, on our way across the state, which – of course – was larger than we had thought. We had considered going down to Marfa, and Big Bend, but all five of us – baby included – were done with the heat. So we changed it up midstream, pointing ourselves toward, New Mexico, by way of Lubbock, where heat awaited, but not so oppressive.

Along the way we spent a couple nights in a nice site by the Colorado River (the Texan one, not the Grand Canyon one), where we went tubing, the girls not scared by the monstrous gray carp that surfaced just feet from them, their lips puckered for bugs on the surface. The river slowed to meandering along the stretches, the sand bars too hot for bare feet, rusted barbed wire visible at the top of red cliffs. The world so squared off in Texas, so hemmed in, despite all the proclamations of size, and freedom. From somewhere far off we heard an auctioneer chanting. I wondered who might be in attendance. Then again, it was Texas. People seemed to do as they pleased, pandemic or not.

We struck camp, thrilled to be on a northern trajectory toward Lubbock. My godmother awaited us in Santa Fe, but we still had a couple days to burn, so we discovered an RV park on the outskirts of a quickly-developing Lubbock that had a castle in front of it that the girls thrilled to. Castle RV Park for the win. Which had a pull-through, and a small pool that no one used. In the mornings I jogged the grass fields with big FOR SALE signs propped up. Passing a police cruiser that said “Capture Excellence.” Which struck me as strange, because you would seem to want to let excellence out in the world, and not capture it.

We honored the crossing into New Mexico with a last meal of Tex-Mex at Leal’s in Muleshoe, Texas, eating warm avocados soaked in gooey cheese, plates that should have been illegal. Kiki marveled at the saddles, asking if horseback riding was an option. Maybe. But first, we needed to get to the true west. The girls sang Simon and Garfunkel’s “Cecilia” at the top of their lungs, Kiki screaming out “making love in the afternoon” for all she was worth. Rachel and I both glad for a moment that the preschools would likely be closed come fall, just so we wouldn’t have to explain.

Errant hair ties all over the truck. The light came on – the truck wanted more diesel exhaust fluid. If not, it threatened to throttle down to 35. By now I was wearing Rachel’s diamond-studded glasses, using her pink phone cord to recharge, feeling fabulous in Texas.

And that’s where we’ll have to throttle down, for this is approaching novel-length.

New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Montana, and Washington, and hopefully having this baby, TK.