New Year 2020, & a return from, and to Siberia

New Year’s 2020. About five months since we’ve returned from Russia. It’s taken this long to arrive at this report on a journey that continues to ripple through us. Even as I write, we prepare to return to Irkutsk in February, to teach at the university. We will live with our friends Olga and Vova, the girls will return to Russian school. To get there we’ll take Aeroflot to Moscow, then quickly switch to S7 to get to Irkutsk. I think it must be bred into the DNA of Aeroflot to make life difficult — not only for Americans, but any living person. Last July, they almost didn’t let us out of the country.

As we prepared to leave Irkutsk, capping almost ten months in-country, with the exception of our one trip to Mongolia, our Americanness had been wavering. Kiki had more or less abandoned English syntax, referring to herself as “little one,” disregarding pronouns, and speaking ‘Merican with a Russian accent. Daddy, do my zeeper. Mommy, seet down.

She had taken to traveling everywhere with Service Bee, a creature she kept in my leather compass case, that we all had come to think of as our St. Christopher, keeping us safe as we went along. To the point where I sincerely didn’t want to travel without it. After all, the dead insect had gotten us from Irkutsk to Mongolia, on the Transiberian Railroad, and through six days of ger living, courtesy of Airbnb and 42 bucks a night with meals included – I wrote a piece on it here for the Philadelphia Inquirer.

In Mongolia, when we went to sleep at night with the goats, Kiki would check to make sure her bee was nearby, stroking its thorax about a thousand times before finally shutting her eyes. Mongolia clearly had no bees or ladybugs flitting around – what a harsh place, the Steppe. The kids of course thrilled to it, especially the animals, a petting/eating zoo par excellence.

At one point the grandmother in the family we stayed with delivered a goat to our ger. We were unclear whether this was lunch, and we were expected to skin and eat the goat, or if the creature was for the kids to play with. Rachel and I had an extended conversation on what Airbnb’s policy might be regarding eating a goat when, in fact, said goat had been delivered for children to play with.

Haley on the Steppe, Mongolian lullabies whispered as we rode along.

A drawn-out conference over what’s to be done about a green and black caterpillar.

In any case, we were putting a lot of faith into Key’s Service Bee to see us over the border from Russia to Western Europe – from there we had found an obscenely cheap flight on XL Airways from Paris to San Francisco.

Leaving Irkutsk our friends Olga and Vova and Vika saw us off, as per Russian tradition – a big vodka-soaked banya, followed by a hungover trip to the airport. The sadness of leaving tempered by the knowledge that they’d be coming to visit us in the fall in the United States. (Or so we believed at the time.)

After switching planes in Moscow, we landed in Petersburg, its water-lined streets a welcome break from the frozen Taiga of Siberia. The nearer we got to the river Neva the more the city appeared like the set of some Russian period drama. Bands of buildings smoothed like icing on a wedding cake, shutterless windows dusted from the wet exhaust of boats cruising the canals. “Venice of the North,” they called the place.

As we strolled about the streets, holding these small eager hands, Rachel and I slowly came to grips with the fact that the upcoming travels we’d been anticipating so long would be a shoe-string tour of the playgrounds of France, Italy, and Russia. Our home in Alaska was already rented out for July off Airbnb, so we’d be treading water until the place opened up. I dinged myself for not pitching a series to Salon on the various qualities and drawbacks of playgrounds throughout Europe.

The playgrounds in Petersburg crawled with the children of diplomats — Korean, South African, West Indian. (Remarkable how a fight over a shovel sounds the same in just about any language.) A sea-change from Irkutsk, where we were the only Americans. As we sat on the bench drinking black tea R and I weighed the benefits and drawbacks of returning to Siberia the following winter — we had both been offered posts at the university teaching. We decided that it was too early to think about such things – at that point we wanted to be back home, to see family, and catch our breath. Key had spent about half her life up to that point speaking a different language, without grandparents. And me, I missed diner food, bottomless cups of coffee, driving with a rule-set and road signs I understood. Also lettuce that didn’t have the texture of wet newsprint.

As we chatted, determining the trajectory of all our respective lives, Haley got into it with a pudgy Russian kid on the gorky, the slide. She had gotten to the point where no one messed with her, in Russian or English. That level of protection extended to her younger sister. If she didn’t like how someone was playing with Kiera-Lee, she’d let loose with a barrage worthy of a Russian sailor. In truth, it was probably more along the lines of, “You just used the slide. Now give my sister a turn.” But her tone – that’s what I mean when I said our Americanness was wavering. They had picked up that Russian tone of ultimate fury, as if the act addressed has transgressed so many boundaries, words almost cannot do to describe it.

It recalled for us the babooshki lighting into us on the streets when we hadn’t adequately clothed our kids. Even writing about it now gives me the shivers.

After our playground time in St. Petersburg, we hopped on one of the boats to get a feel of the layout of the city, the leafy parks, the Russian green of the winter palace, an exact copy of the mint-green that you find in the lobby of every dang apartment building in Russia.

After the ride, we walked back to our Airbnb , a third-floor walk-up – of course with the mint green walls – and a pull-out couch. Tourists squint into the sun as they waved up from passing boats. We passed a clinic on how to learn to smile, a class that should be required for all Russians. Long blocks pocked with coffeeshops that poured drip-coffee, baristas with jeans buttoned at their ribs, scrunchies around their wrists – a style my wife tells me is VSCO, signified by Keds and big sweatshirts, one that apparently has been exported to metropolitan Russia.

On our third night there, a good friend of mine, also a Fulbright, invited us for dinner. He lived right off the Nevsky Prospect, the main thoroughfare for business. Our apartment was situated just off the blue bridge, near one of the inner canals, not far from St. Isaac’s Cathedral, and we hopped a cab across town that quickly got snarled in afternoon “chas peak” – rush hour on Nevsky. As I watched the shops go by, I thought how Lenin must be rolling in his grave – Levis, Louis Vuitton, Gucci. Not a shred left of the Soviet era, save for an occasional kitschy shirt showing the hammer and sickle. Is this why he had ordered the last Czar to be shot? Why he had given his life?

My friend was married to a Russian woman, and their son, 2, spoke only Russian. Kiera-Lee kept looking at the boy, marveling how he spoke as easily and fluently as his parents. We all gathered at a small table and ate from a blue bowl of beans, smeared with the back of a spoon onto fajitas. How long had it been since we had eaten a good avocado? Fresh cilantro? Even cheddar of that yolky yellow-orange hue. As I said, the things you miss.

Saturday in Petersburg I left the apartment early to visit the Naval Cathedral of St. Nicolas in Kronstadt, an island in the Bay of Neva where the Russians had, over hundreds of years, built up their naval presence, constructed a dry dock, and started a naval academy. The Navy at constant guard against an attack from the foxy Swedes, or any other seaborne force that might want to attack such an exposed city, not to mention the home of the emperor. The naval academy played a large role in the book I was writing, and I wanted a few details for scene-setting.

My Uzbeki Yandex taxi driver (Yandex the equivalent of Uber) picked me up downtown for the hour drive out. Dressed in fashionably in a jean jacket and t-shirt, he panicked right before we reached Putin’s new bridge, asking me in machine-gun Russian to look on my phone for the nearest gas station, because if we ran out of gas on the bridge we were in it for real. He ended up taking a u-turn on the highway, then thanking Allah repeatedly for the presence of a pump.

Kronstadt itself had the feel of a seaside beach community, almost like a Russian Ocean City. Sand strewn over the sidewalks. Crumbling brick walls surrounded the town. Apparently foreigners used to be forbidden from visiting. Alexander the Great built a dry-dock here that was still in use – one that made me drool, thinking of pulling the Adak in for work.

After touring the museum, and marveling over drawings of Russia’s New World – Alaska – I hopped the taxi home. Thinking along the way of a flotilla of Swedish man-o-wars firing their cannon at the walls, half-listening as my Uzbeki friend went on about how a contemporary Russian uprising is more-or-less inevitable due to economic inequality. Surprising he’d speak so openly, but perhaps the morning’s adventure had made him giddy. He swore on his mother’s grave he’d get up the following morning to take us to the airport.

The next morning we were out at six am amidst all our bags, including Haley’s samokat, her scooter that she whizzed about town on. After 15 minutes I realized my Uzbeki friend wasn’t going to show. I pictured him in his jean jacket and t-shirt dancing in the lights of some Russian nightclub, vodka and red-bull in a hand. With no worries of running out of gas.

Things continued to go downhill from there. The Petersburg airport must have been designed by a vodka-drenched architect with a bad sense of humor who had was trying to create Kafka’s Castle in the form of an international airport. Who knows how they pulled off a World Cup getting people in an out of there.

Though we had stowed a number of bags in Russia anticipating a return we were still weighed down with tea, Mongolian socks, and inexpensive Russian clothing for our return. If Colorado had been living, we would have been dead in the water, no doubt. Though thinking about it, we probably would have headed east back home, instead of backtracking.

Inside the welcome hall, pale-eyed men and women milled about, embalming their bags in plastic, shouting at one another. Once we finally found our line for Aeroflot, we waited for some time before realizing we weren’t even allowed to check in until two hours to the flight. When we got to the ticket agent, she gave us that quintessential I-could-care-less expression. As if some doctor operating on her brain had nicked the spot controlling the muscles of her face, making them all just fall. The kids, perched like parakeets atop our luggage cart, eyed us nervously as we made for immigration, the two of them uncharacteristically silent. Just an hour before the plane lifted off. C’mon Service Bee, I thought.

At passport control I did my best to yell in Russian to a family that cut the line. Turns out they knew something we did not. Which was, if you want to make your Aeroflot flight, and you’re traveling with kids, then you need to cut the line. Service Bee or not.

We arrived four minutes after the doors shut. The kids cried. Rachel cried. We were told our tickets would not be refunded, and we needed to leave the terminal. Which was a problem, because passport control had already taken our immigration papers. If we were caught without it in Russia without these little slips of paper, we could be fined and put in jail. Rachel said, eyeliner running down her cheeks, “We’re never going to get out of this place.”

When in doubt, practice a good ol’ American sit-in. The four of us refused to walk through passport control until we were provided with immigration papers. And this was no peaceful sit-in – the girls howled like banshees, the poor suited Aeroflot agent shifting in his black loafers, switching between his monotone English and impassioned Russian, as he tried to convince us that there was nothing more to be done, and we needed to leave.

Finally a female immigration official wearing enough makeup for the circus handed us immigration papers. Still, there were no guarantees of flights. She directed us through the clouds to the Aeroflot desk, where a 24 year-old zombie-in-training informed us there were no refunds, we would be provided with no assistance. In addition, there were no flights for the next three days. Basically, we were screwed.

I overheard some ragged Russian similar to my own, and saw three older French women engaged in their own battle royale next to me. We struck up a conversation. They informed us that Air France had a flight to Paris that afternoon. $802 for the four of us, at least a month of work in Russia. But Reader, we took those tickets, and walking into that Air France flight, with their plush fleece blankets, doll-sized bottles of wine, soft-spoken flight attendants – what a flush of endorphins. So gently the plane lifted off, and, almost momentarily, it seemed, Haley was jabbing her finger at the window, pointing out the Eiffel Tower, which appeared, as if in miniature, below.

In Paris the heat whacked us broadside as we caught a bus to the terminal. Kiera-Lee, who had spent the better part of her life in Alaska and Russia, seemed to wilt in my arms. Of course our little Paris loft was on the top floor, just off the Boulevard Royal, the elevator hardly big enough for one of our overstuffed bags. The girls refused to come out of the cold shower, and sprawled out on the sheets like little Icarus statues, fallen from some great height. Haley dropped off into sleep in the middle of a conversation with Rachel over whether it’s okay to cry even when you’re not really sad*

The following morning was like waking into Paris cinema. We had stumbled onto a market day for our block, ricocheting between the seafood and cheese kiosks. A bearded man in his wool vest cooed away at the kids, who, in their denim dresses and sandals, appeared more Russian and Scandinavian than American. We hopped the subway to Tour Mauborg, and had lunch in a park where, after the girls whizzed behind a clutch of bushes, Kiki announced she would not, could not climb the Eiffel Tower without her Service bee. Thus began a mad search of the tawny gravel path for a dead bee. And lo and behold, what did Rachel find – a dead bee. Waiting.

At the Eiffel Tower we all but walked into the glass panes walling off the bottom, like birds crashing into a window. We made it through security, then bypassed the lines for the elevators, and waited to walk up the stairs, crop-dusted every fifteen minutes by a spray of water that Haley opened her mouth to drink from.

The girls were troopers, making it about halfway up under their own steam. Then Kiki jumped aboard the Daddy-elevator, then Haley. Thankfully, the top level on the tower was closed due to high winds. We made it to the first level, where Kiki’s bee had a good view of the city, and the kids could glory in mint chocolate chip ice cream.

From there we hopped a rickshaw type deal back to Luxembourg gardens, where the kids chose sailboats to push with sticks (by that time our phones were out of juice – no photos during perhaps the most photogenic moments of their little lives). From afar we heard the deep techno boom of the gay pride parade, which we needed to bypass in order to get back to our apartment. Kiki announced that she wanted to go dance with the men on the boats with the fire hoses, a sure sign of her party nature. Haley looked on skeptically. During an opening in the rainbows we dashed across the avenue, and squished into the absurdly small elevator.

Early in the morning we somehow managed to hail a taxi big enough to take all our bags, and the girls sans car seats. Gare de Lyon humming with folks trying to score tickets on the TGV down south. The girls sleep-walked through it all, coloring in their books, looking up longingly at the Train Bleu with its almond croissants. Rachel in her new cloche hat from La Rue Mouffetard.

South we traveled, exiting a few hours later, magically whisked to Aix-en-Provence, which I had good memories of – but which struck me now as over-touristed, unbearable in the heat. A situation not helped by our Airbnb, situated at the top of a long set of narrow stairs, far from the playground. Aix gets a solid “F” when it comes to being kid-friendly. At one point Kiki tumbled into a fountain, and the Japanese tourists fell over themselves to get photos. The playgrounds that they did have were ringed by Bocce ball courts populated by shirtless, bizarrely hairless men drinking pastis and tall boy beers alternately. The girls ended up playing some rip-roaring games of hide-and-go-week on the burnt grass. And Kiki ended up being a great help at the sycamore-shaded market, scoring the two of us any number of olives or slices of saucisson. Haley and I went on a mission to scope out the bus station; she was attracted by the cries of a little boy to some bungee apparatus that flings you into the sky. “I want to try.” After testing the limits of my French to convince this big provencal dude that my four year-old daughter wouldn’t pitch a fit if he hooked her up, she was in there – and up she went, laughing like a banshee. Proud papa.

Then we got a call from a close French buddy I had fished with in Alaska. He invited us to the farm where he grew up, which also was a bed and breakfast, with apricot trees and grape vines. After a bit of thought – like two seconds – we snuck our little white rental into the old city of Aix, loaded her up, and were on the road again. Delayed briefly when Haley fed some grapevines her lunch. Thank the good lord for wet wipes. We did a brief stop at a chocolatier for a welcome gift, which melted the moment they left the air-conditioned store, then one more at the pharmacy for sunglasses for the girls. Their Sicilian skin was browning nicely, but their Alaskan eyes just weren’t used to the bright sun of southern France.

Following a few days in this sweet paradise, we began our most packed travel thus far – a train to Marseille, then another twenty minutes later to Genoa, Italy. And then one leaving in half an hour that would take us to Sicily. What about the Strait of Messina? Good question! They drive the train onto the ferry. That’s right. Just pull the whole darn thing onboard. Just like those Brio sets you played with as a kid. The girls couldn’t get enough of it. As we crossed the deep blue water the girls picked out our train car waiting beneath us.

We all went to the Catania Airport, which was challenge the Petersburg Airport for being hell on earth – hot and smelling of old pizza crusts and bitter coffee, any number of bachelorette groups in sequined oversized glasses ready to knock down boxes of wine and unravel reams of gossip.

For a number of reasons, including that we were verging on broke, Wells Fargo does not honor travel notices, waiting for a few Airbnb payments, our credit cards were uniformly declined. After trolling the hundreds of different rental car option. we ended up spending a good couple hours trying to find a rental car, finally landing on a little place that would allow us behind the wheel for a couple days with a promise to return the thing, one we had no intention of keeping.

And off we went, to find the ancient villa in the olive oil orchard we had rented with our friends – also off Airbnb, the idea developed around the concept of finding Rachel’s long-lost relative named – you guessed it – Sal in the small hill-town of Tremestieri Etni. Starting of course where all things seem to start in Italy, the Catholic Church. Ending at the Servici Demographici, an earnest women with hand gestures who seemed wary of Italian-Americans coming back to the Old World in hopes of finding family land. And that was the story – that Rachel’s nonna had written it into the deed that any descendants that came back to Sicily would be given the land that the neighbors had, in the meantime, agreed to take care of.

All I can say about Sicily is that, it seems clear to me, that the go-getters of the island, which has been dominated by any number of cultures over the course of thousands of years, left. Most for the United States, where they seem to have kicked some butt. And the rest stayed behind. The island had the feeling of post-plague. Forty percent gone. Up and out.

It was in Italy Rachel and I began to have conversations about returning to the United States. I think she expected to have more in common with folks there. Granted, she took great pleasure in shaking out sheets and clothes-pinning them to the lines each morning. Even morning sweeping off our terrace, soaking it down with the hose. The heat, which I found oppressive, she welcomed, closing her eyes to it, not minding the hot stones on her bare feet.

Perhaps it was our failure to locate Sal and the land her family had left. Or any trace at all of the Ansaldos. Perhaps it was our attempt in Catania to find one dang place to have a meal at two in the afternoon, Rachel finally begging to go through a McDonald’s drive through – in Italy! Who knows. But we started talking about the type of people who came to America, the go-getters, the ones who don’t nap, the ones who probably should be in prison. The best, the worst. And – for better or worse – that was where we came from. Though we liked Russia – especially the people – the fatalism felt fabricated and cloying. And Sicily seemed wary and forgotten.

On top of that, we were raising American kiddos, like it or not. Even if Kiki spoke with a Russian accent, arranged her syntax like a Russian, she attacked that playground gymnasium like it was the last thing she was going to climb on this earth. Even if Haley had a particular Russian strut, she did everything so hard, desperately. A little naively, if such a thing can be said for a four-year-old. Also American.

This was both an invigorating, and disappointing realization. Though if you extend it out, the upshot is something Rachel and I both knew going into this whole kid-growing endeavor: blood thicker than all of it. Family, friends, and also what you weather together – Aeroflot, falling into fountains, making near-illegal train connections in confusing train stations – this keeps you tight. And these two girls, they’d always have each other.

With a little money in the bank we extended our car rental, neglecting to tell the company that our four year-old was spending hours driving the kid-sized Peugeot 205 up and down Sicilian gravel roads. We booked the dirt-cheap 11-hour flight from Paris to San Francisco, and flew from that sweaty hell-hole of an airport in Catania to an airport in the farmlands surrounding Paris. Boarded the plane, spent a couple days in California – “Dad! They all speak English!” Kiki told me at one point – before boarding Alaska Airlines, which felt, indeed, like coming home. “Are we going to the yellow house?” she asked as we took our seats.

And it made sense. Girl had no other point of reference other than the color of the different buildings where we had lived. She had spent the greater part of her speaking existence in a place that spoke other languages, be it Russian, French, or Italian. Colors her way of identifying insects, numbers, letters, and home.

Upon a return to Finn Alley, we immediately got down to the business of filling the freezer with fish and berries. Taking care of the house – and of course, the Adak, along with Haley’s Comet, the boat responsible for ferrying Haley between the tug and the work dock when she was a kid. Not to mention putting her to sleep, the Yamaha 70 two-stroke having some sort of calming power on her baby nerves.

When the skiff didn’t turn over we set out to do an overhaul on the engine. Bought new plugs down at Napa, and a brush so she could ream out the rust. Her little hands perfectly matched to unscrew the filter on the engine, and to handle the socket wrench. Meanwhile Rachel, while working on the floors of our center apartment, made the lovely discover of old growth CVG Doug Fir beneath our crappy stained carpet – and suddenly we had friends over ripping up the floors, going at it hard, Haley pounding in the threshold. Hungry after all the work, Haley announced that she missed eating halibut – so we set to sharpening the skate hooks, renewing our subsistence SHARC license, and getting out to our little secret honey-hole to set. Returning that evening and pulling up a nice chicken, which we sealed up for winter, and ate by the fire that night with S’Mores. Haley very satisfied with herself. Meanwhile, come August 1, I started getting out there for deer. Taking the skiff, kayaking in and cruising. Had one in my sights, but the shot too long.

Through this all Rachel and I had ongoing conversations about next moves. And made the decision that the kids needed to re-connect with family on the East Coast.

Upon our arrival back east we headed up to visit my aunt and uncle on their farm in Danville. Haley, always sensitive to strong smells, or any sort of sensory input, took exception with the scent of fresh hay. Kiera-Lee – she could live on a farm no problem. We headed down to the pond where I had learned to fish, spending hours on the banks with a .22 rifle waiting for a snapping turtle to peak out its periscope head. We dug beneath the rocks for worms, and quickly hooked a little sunny. The smallmouth bass cruising the edges just weren’t having what we were offering them.

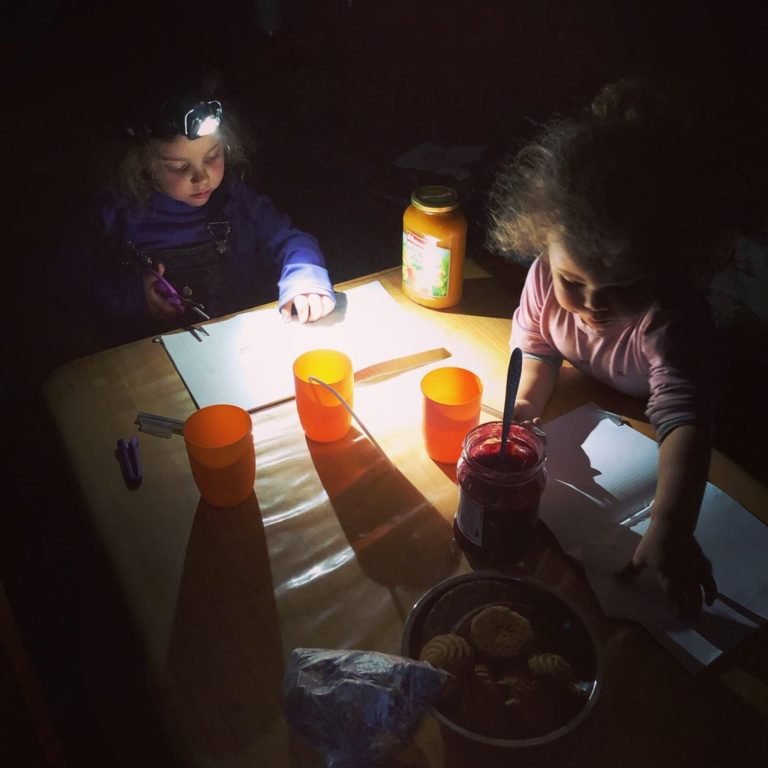

With our extended stay in Philly, the girls have been getting good grandparent time. Haley’s been doing Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Kiera-Lee still uses Russian grammar construction, a habit encouraged by Vika, a Russian babysitter from the Northeast who comes Tuesdays and Thursdays to hang with the kids.

We’ll be heading back to Siberia for three months, living with our friends outside of Irkutsk, and the back home to Alaska, which the girls miss so much. This trip to Siberia interrupted a good rhythm we had going there, Rachel serving as judge, me teaching at the university. Then the Fulbright.

These are the choices you make. Though, in the end, long as you keep your kids close, a roof over your head and food on the table, the rest seems to work itself out. Place secondary. The task for each day pretty simple: keeping the tiny humans going. Increasingly, that means their little brains firing. Hence back to Russia we go.